Aristotle Argue Both Science and Art Can Express Universal Truths

| Western philosophy Ancient philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Proper name: Aristotle | |

| Nativity: 384 B.C.E. | |

| Death: March 7, 322 B.C.E. | |

| School/tradition: Inspired the Peripatetic schoolhouse and tradition of Aristotelianism | |

| Main interests | |

| Politics, Metaphysics, Science, Logic, Ethics | |

| Notable ideas | |

| The Golden mean, Reason, Logic, Biology, Passion | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Parmenides, Socrates, Plato | Alexander the Neat, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Averroes, Albertus Magnus, Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Ptolemy, St. Thomas Aquinas, and near of Islamic philosophy, Christian philosophy, Western philosophy and Science in general |

Aristotle (Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης Aristotélēs) (384 B.C.E. – March 7, 322 B.C.E.) was a Greek philosopher, a student of Plato, and teacher of Alexander the Great. He wrote on diverse subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poesy (including theater), logic, rhetoric, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology. Forth with Socrates and Plato, he was among the nearly influential of the ancient Greek philosophers, equally they transformed Presocratic Greek philosophy into the foundations of Western philosophy as it is known today. Well-nigh researchers credit Plato and Aristotle with founding two of the most of import schools of ancient philosophy, forth with Stoicism and Epicureanism.

Aristotle's philosophy made a dramatic impact on both Western and Islamic philosophy. The beginning of "modernistic" philosophy in the Western world is typically located at the transition from medieval, Aristotelian philosophy to mechanistic, Cartesian philosophy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, even the new philosophy connected to put debates in largely Aristotelian terms, or to wrestle with Aristotelian views. Today, there are avowed Aristotelians in many areas of contemporary philosophy, including ethics and metaphysics.

Contents

- ane Life

- 2 Methodology

- 3 Logic

- 4 Metaphysics

- 4.ane Causality

- iv.2 Substance, matter, and form

- four.3 Universals and particulars

- 4.4 The five elements

- 5 Philosophy of mind

- 6 Practical philosophy

- six.1 Ethics

- vi.ii Politics

- 7 The loss of his works

- 8 Legacy

- 9 Bibliography

- 9.1 Major works

- 9.i.ane Logical writings

- 9.1.two Physical and scientific writings

- 9.ane.3 Metaphysical writings

- ix.1.4 Ethical & Political writings

- nine.1.5 Artful writings

- nine.2 Major current editions

- 9.1 Major works

- 10 Notes

- 11 References

- 12 External links

- 12.1 General philosophy sources

- 13 Credits

Given the volume of Aristotle's piece of work, it is not possible to fairly summarize his views in anything less than a volume. This article focuses on the aspects of his views that have been most influential in the history of philosophy.

Life

Aristotle was built-in in Stageira, Chalcidice, in 384 B.C.E. His father was Nicomachus, who became physician to Rex Amyntas of Macedon. At nigh the historic period of eighteen, he went to Athens to continue his instruction at Plato's University. Aristotle remained at the academy for nearly twenty years, not leaving until subsequently Plato's death in 347 B.C.E. He then traveled with Xenocrates to the court of Hermias of Atarneus in Asia Minor. While in Asia, Aristotle traveled with Theophrastus to the island of Lesbos, where together they researched the botany and zoology of the isle. Aristotle married Hermias' girl (or niece) Pythias. She bore him a daughter, whom they named Pythias. Soon subsequently Hermias' death, Aristotle was invited by Philip of Macedon to become tutor to Alexander the Smashing.

Subsequently spending several years tutoring the immature Alexander, Aristotle returned to Athens. By 334 B.C.Eastward., he established his own schoolhouse there, known as the Lyceum. Aristotle conducted courses at the school for the next eleven years. While in Athens, his wife Pythias died, and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis of Stageira, who bore him a son that he named later on his father, Nicomachus.

It is during this period that Aristotle is believed to take composed many of his works. Aristotle wrote many dialogues, only fragments of which survived. The works that accept survived are in treatise class and were not, for the nigh part, intended for widespread publication, and are mostly thought to be mere lecture aids for his students.

Aristotle non merely studied almost every subject possible at the fourth dimension, but made significant contributions to most of them. In concrete science, Aristotle studied anatomy, astronomy, economics, embryology, geography, geology, meteorology, physics, and zoology. In philosophy, he wrote on aesthetics, ethics, authorities, logic, metaphysics, politics, psychology, rhetoric, and theology. He also studied education, foreign customs, literature, and poetry. Considering his discussions typically brainstorm with a consideration of existing views, his combined works constitute a virtual encyclopedia of Greek knowledge.

Upon Alexander'southward decease in 323 B.C.East., anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens once once again flared. Having never made a secret of his Macedonian roots, Aristotle fled the city to his mother's family estate in Chalcis, explaining, "I will not permit the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy."[1] However, he died there of natural causes inside the yr.

Methodology

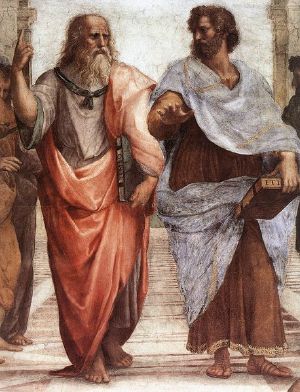

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a particular of The Schoolhouse of Athens, a fresco past Raphael. Aristotle gestures to the earth, representing his belief in cognition through empirical observation and experience, while holding a copy of his Nicomachean Ideals in his manus, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, representing his belief in The Forms.

Both Plato and Aristotle regard philosophy as concerning universal truths. Roughly speaking, however, Aristotle establish the universal truths by because detail things, which he called the essence of things, while Plato finds that the universal exists autonomously from particular things, and is related to them equally their image or exemplar. For Aristotle, therefore, philosophic method implies the ascension from the report of particular phenomena to the cognition of essences, while for Plato philosophic method means the descent from a knowledge of universal ideas to a contemplation of particular imitations of those ideas (compare the metaphor of the line in the Republic).

It is, therefore, unsurprising that Aristotle saw philosophy as encompassing many disciplines which today are considered role of natural science (such every bit biology and astronomy). Yet, Aristotle would have resisted the over-simplifying clarification of natural science as based entirely in observation. After all, all data requires some interpretation, and much of Aristotle's work attempts to provide a framework for interpretation.

Logic

Aristotle is, without question, the most important logician in history. He deserves this championship for two main reasons: (i) He was the starting time to consider the systematization of inferences as a field of study in itself (it would not be an exaggeration to say that he invented logic), and (2) his logical organisation was the dominant i for approximately 2000 years. Kant famously claimed that nothing significant had been added to logic since Aristotle, and concluded that it was one of the few disciplines that was finished. The piece of work of mathematicians such equally Boole and Frege in the nineteenth century showed that Kant was wrong in his estimation, but even contemporary logicians concord Aristotle in loftier regard.

Key to Aristotle's theory was the claim that all arguments could exist reduced to a simple form, called a "syllogism." A syllogism was a set of three statements, the third of which (the decision) was necessarily true if the first two (the bounds) were. Aristotle thought that the basic statements were of i of four forms:

- All Ten's are Y'southward

- No X'due south are Y's

- Some X's are Y's

- Some 10's are not Y's

Aristotle'due south main insight, the insight that more or less began logic equally a proper discipline, was that whether an inference was successful could depend on purely formal features of the statement. For instance, consider the post-obit two arguments:

- All cats are animals

- All animals are fabricated of cells

- Therefore, all cats are made of cells

and:

- All ducks are birds

- All birds take feathers

- Therefore, all ducks take feathers

The particular substantive words differ in these two arguments. Nevertheless, they have something in mutual: a sure structure. On reflection, it becomes clear that any argument with this structure will be i where the truth of the conclusion is guaranteed by that of the premises.

Metaphysics

Every bit with logic, Aristotle is the first to have treated metaphysics as a singled-out discipline (though, more than in the case of logic, other philosophers has discussed the same specific issues). Indeed, the very word "metaphysics" stems from the ordering of Aristotle'south writing (it was the book prior to his Physics).

Causality

Aristotle distinguishes four types of cause: Textile, formal, efficient, and final. His notion of efficient causation is closest to our contemporary notion of causation. To avoid confusion, it is helpful to think of the division as one of different types of explanations of a matter's beingness what it is.

The textile cause is that from which a affair comes into existence as from its parts, constituents, substratum or materials. This reduces the caption of causes to the parts (factors, elements, constituents, ingredients) forming the whole (system, structure, compound, complex, composite, or combination), a human relationship known as the part-whole causation. An example of a fabric cause would be the marble in a carved statue, or the organs of an animal.

The formal cause argues what a thing is, that any matter is determined by the definition, form, pattern, essence, whole, synthesis, or archetype. It embraces the account of causes in terms of central principles or general laws, as the whole (that is, macrostructure) is the cause of its parts, a relationship known as the whole-part causation. An example of a formal crusade might be the shape of the carved statue, a shape that other detail statues could besides take, or the arrangement of organs in an animal.

The efficient (or "moving") cause is what we might today most naturally depict equally the crusade: the agent or force that brought about the thing, with its particular matter and form. This cause might be either internal to the thing, or external to it. An example of an efficient cause might be the artist who carved the statue, or the beast'south own ability to grow.

The final cause is that for the sake of which a thing exists or is done, including both purposeful and instrumental deportment and activities. The terminal cause, or telos, is the purpose or finish that something is supposed to serve, or information technology is that from which and that to which the change is. This also covers modern ideas of mental causation involving such psychological causes every bit volition, need, motivation, or motives, rational, irrational, ethical, all that gives purpose to behavior. The best examples of final causes are the functions of animals or organs: for case, the final cause of an eye is sight (teleology).

Additionally, things can be causes of one another, causing each other reciprocally, as hard piece of work causes fettle and vice versa, although not in the aforementioned fashion or function, the one is equally the beginning of modify, the other as the goal. (Thus, Aristotle showtime suggested a reciprocal or circular causality as a relation of mutual dependence or influence of cause upon effect.) Moreover, Aristotle indicated that the same thing can be the cause of contrary furnishings; its presence and absence may result in dissimilar outcomes. For example, a certain food may be the cause of health in one person, and sickness in some other.

Substance, affair, and course

Aristotelian metaphysics discusses item objects using ii related distinctions. The first stardom is that betwixt substances and "accidents" (the latter being "what is said of" a thing). For instance, a cat is a substance, and one tin say of a cat that it is gray, or small. Only the greyness or smallness of the cat belong to a different category of being—they are features of the cat. They are, in some sense, dependent for their existence on the cat.

Aristotle also sees entities as constituted by a sure combination of matter and grade. This is a distinction which can exist made at many levels. A cat, for instance, has a set of organs (heart, peel, bones, and then on) as its matter, and these are arranged into a sure course. Yet, each of these organs in turn has a certain thing and class, the matter being the flesh or tissues, and the course being their arrangement. Such distinctions keep all the way downwardly to the most basic elements.

Aristotle sometimes speaks as though substance is to be identified with the matter of particular objects, only more oft describes substances equally individuals composed of some matter and course. He likewise appears to accept thought that biological organisms were the paradigm cases of substances.

Universals and particulars

Aristotle'southward predecessor, Plato, argued that all sensible objects are related to some universal entity, or "form." For instance, when people recognize some detail book for what it is, they consider it as an case of a full general type (books in full general). This is a fundamental feature of human experience, and Plato was securely impressed by information technology. People don't see full general things in their normal experience, only particular things—so how could people have feel of particulars every bit being of some universal type?

Plato's answer was that these forms are carve up and more than fundamental parts of reality, existing "outside" the realm of sensible objects. He claimed (perhaps near famously in the Phaedo) that people must have encountered these forms prior to their birth into the sensible realm. The objects people normally experience are compared (in the Republic) with shadows of the forms. Whatsoever else this means, information technology shows that Plato thought that the forms were ontologically more bones than item objects. Considering of this, he thought that forms could exist even if there were no detail objects that were related to that form. Or, to put the point more technically, Plato believed that some universals were "uninstantiated."

Aristotle disagreed with Plato on this bespeak, arguing that all universals are instantiated. In other words, at that place are no universals that are unattached to existing things. Co-ordinate to Aristotle, if a universal exists, either as a particular or a relation, and so there must accept been, must be currently, or must be in the future, something on which the universal can be predicated.

In addition, Aristotle disagreed with Plato well-nigh the location of universals. As Plato spoke of a split up world of the forms, a location where all universal forms subsist, Aristotle maintained that universals be inside each thing on which each universal is predicated. So, according to Aristotle, the form of apple exists within each apple tree, rather than in the world of the forms. His view seems to accept been that the most fundamental level of reality is only what people naturally take information technology to be: The item objects people encounter in everyday experience. Moreover, the chief mode of becoming informed about the nature of reality is through sensory feel.

The basic contrast described here is 1 that echoed throughout the history of Western philosophy, oftentimes described as the dissimilarity betwixt rationalism and empiricism.

The 5 elements

Aristotle, developing one of the main topics of the Presocratics, believed that the world was built up of v bones elements. The building upwardly consisted in the combining of the elements into various forms. The elements were:

- Fire, which is hot and dry

- Earth, which is common cold and dry out

- Air, which is hot and moisture

- Water, which is cold and wet

- Aether, which is the divine substance that makes up the heavenly spheres and heavenly bodies (stars and planets)

Each of the four earthly elements has its natural place; the earth at the centre of the universe, then water, then air, then burn. When they are out of their natural place they have natural motion, requiring no external cause, which is towards that place; so bodies sink in water, air bubbles up, rain falls, flame rises in air. The heavenly chemical element has perpetual circular motion.

This view was key to Aristotle's explanation of celestial move and of gravity. It is often given as a image of teleological explanation, and became the ascendant scientific view in Europe at the end of the eye ages.

Philosophy of mind

Aristotle'due south major word of the nature of the listen appears in De Anima. His business organisation is with the "principle of motility" of living entities. He distinguishes 3 types of soul:

- Nutritive

- Sensory

- Thinking

All plants and animals are capable of arresting nutrition, then Aristotle held that they all have a nutritive soul. Yet, not all are capable of perceiving their surround. Aristotle thought this was indicated by a lack of motility, holding that stationary animals cannot perceive. He, therefore, ended that the presence of this blazon of soul was what distinguished plants from animals. Finally, Aristotle held that what was distinctive of humans is their ability to retrieve, and held that this requires yet some other principle of move, the thinking soul.

Most of Aristotle'south discussion of the soul is "naturalistic"—that is, information technology appears to only describe entities whose existence is already countenanced in the natural sciences (primarily, physics). This is specially brought out past his claim that the soul seems to be the grade of the organism. Considering of this, some gimmicky advocates of functionalism in the philosophy of listen (just every bit Hilary Putnam) accept cited Aristotle as a predecessor.

In the De Anima discussion, notwithstanding, there are places where Aristotle seems to suggest that the rational soul requires something beyond the torso. His remarks are very condensed, and so incredibly hard to translate, simply these few remarks were the focus of Christian commentators who attempted to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy with Christian doctrine.

Practical philosophy

Ethics

Aristotle'southward main treatise on ideals is the Nichomachean Ethics, in which he gives the first systematic articulation of what is now chosen virtue ethics. Aristotle considered ethics to be a applied science, that is, one mastered by doing rather than simply reasoning. This stood in sharp contrast to the views of Plato. Plato held that knowledge of the practiced was achieved through contemplation, much in the manner in which mathematical agreement is achieved through pure thought.

Past contrast, Aristotle noted that knowing what the virtuous thing to do was, in any particular instance, was a thing of evaluating the many particular factors involved. Because of this, he insisted, it is not possible to formulate some non-trivial rule that, when followed, volition always pb the virtuous activity. Instead, a truly virtuous person is i who, through habituation, has adult a not-codifiable ability to approximate the situation and act accordingly.

This view ties in with what is perhaps Aristotle's all-time-known contribution to ethical theory: The so-chosen "doctrine of the hateful." He held that all the virtues were a thing of a balance between two extremes. For instance, backbone is a state of character in between cowardice and brashness. Likewise, temperance is a country of character in betwixt dullness and hot-headedness. Exactly where in between the two extremes the virtuous state lies is something that cannot be stated in any abstract formulation.

Also significant here is Aristotle's view (i too held by Plato) that the virtues are inter-dependent. For case, Aristotle held that information technology is not possible to be mettlesome if one is completely unjust. Nonetheless, such interrelations are also also circuitous to exist meaningfully captured in whatever elementary rule.

Aristotle taught that virtue has to exercise with the proper function of a thing. An eye is only a expert eye in and so much as it tin see, because the proper function of an heart is sight. Aristotle reasoned that humans must have a function that sets them apart from other animals, and that this office must exist an activity of the soul, in particular, its rational part. This function essentially involves action, and performing the office well is what constitutes man happiness.

Politics

Did you know?

Aristotle believed that human nature is inherently political since individuals cannot achieve happiness without forming states (political bodies) because the private in isolation is not cocky-sufficient

Aristotle is famous for his argument that "man is past nature a political animate being." He held that happiness involves self-sufficiency and that private people are not self-sufficient, so the want for happiness necessarily leads people to form political bodies. This view stands in contrast to views of politics that hold that the formation of the country or urban center-state is somehow a deviation from more natural tendencies.

Similar Plato, Aristotle believed that the ideal state would involve a ruling class. Whereas Plato believed that the philosophers should rule, Aristotle held that the rulers should exist all those capable of virtue. Unfortunately, Aristotle believed that this was a fairly restricted group, for he held that neither women, slaves, nor labor-class citizens were capable of becoming virtuous.

For Aristotle, this platonic state would be 1 which would allow the greatest habituation of virtue and the greatest corporeality of the activity of contemplation, for but these things corporeality to human happiness (as he had argued in his ethical works).

The loss of his works

Though Aristotle wrote many elegant treatises and dialogues (Cicero described his literary style as "a river of gold"),[2] the vast majority of his writings are at present lost, while the literary character of those that remain is disputed. Aristotle's works were lost and rediscovered several times, and it is believed that only about ane fifth of his original works have survived through the time of the Roman Empire.

After the Roman menses, what remained of Aristotle'southward works were by and large lost to the West. They were preserved in the East past various Muslim scholars and philosophers, many of whom wrote extensive commentaries on his works. Aristotle lay at the foundation of the falsafa movement in Islamic philosophy, stimulating the thought of Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd, and others.

As the influence of the falsafa grew in the West, in part due to Gerard of Cremona's translations and the spread of Averroism, the need for Aristotle'south works grew. William of Moerbeke translated a number of them into Latin. When Thomas Aquinas wrote his theology, working from Moerbeke'due south translations, the need for Aristotle's writings grew and the Greek manuscripts returned to the Due west, stimulating a revival of Aristotelianism in Europe.

Legacy

Information technology is the opinion of many that Aristotle's arrangement of thought remains the most marvelous and influential one ever put together by any unmarried mind. According to historian Will Durant, no other philosopher has contributed so much to the enlightenment of the world.[3] He single-handedly began the systematic treatment of Logic, Biology, and Psychology.

Aristotle is referred to as "The Philosopher" past Scholastic thinkers similar Thomas Aquinas (for case, Summa Theologica, Office I, Question 3). These thinkers blended Aristotelian philosophy with Christianity, bringing the idea of Ancient Hellenic republic into the Center Ages. The medieval English poet Chaucer describes his student as beingness happy by having

At his bedded hed

Twenty books clothed in blake or cherry-red,

Of Aristotle and his philosophie (Chaucer).

The Italian poet Dante says of Aristotle, in the get-go circles of hell,

I saw the Primary there of those who know,

Amidst the philosophic family,

By all admired, and by all reverenced;

At that place Plato too I saw, and Socrates,

Who stood beside him closer than the balance (Dante, The Divine Comedy)

Almost all the major philosophers in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries felt impelled to accost Aristotle'south works. The French philosopher Descartes cast his philosophy (in the Meditations of 1641) in terms of moving away from the senses every bit a basis for a scientific understanding of the world. The great Jewish philosopher Spinoza argued in his Ethics straight against the Aristotlean method of understanding the operations of nature in terms of concluding causes. Leibniz often described his own philosophy equally an attempt to join the insights of Plato and Aristotle. Kant adopted Aristotle's apply of the grade/thing distinction in describing the nature of representations—for example, in describing space and time as "forms" of intuition.

Bibliography

Major works

The extant works of Aristotle are broken down according to the five categories in the Corpus Aristotelicum. The titles are given in accordance with the standard ready past the Revised Oxford Translation.[4] Not all of these works are considered genuine, only differ with respect to their connectedness to Aristotle, his associates and his views. Some, such as the Athenaion Politeia or the fragments of other politeia, are regarded past most scholars as products of Aristotle's "school" and compiled nether his direction or supervision. Other works, such every bit On Colours, may have been products of Aristotle'due south successors at the Lyceum, for instance, Theophrastus and Straton. Still others acquired Aristotle'south proper name through similarities in doctrine or content, such as the De Plantis, possibly by Nicolaus of Damascus. A terminal category, omitted hither, includes medieval palmistries, astrological, and magical texts whose connection to Aristotle is purely fanciful and self-promotional. Those that are seriously disputed are marked with an asterisk.

In several of the treatises, there are references to other works in the corpus. Based on such references, some scholars have suggested a possible chronological lodge for a number of Aristotle'due south writings. W.D. Ross, for case, suggested the following broad arrangement (which of course leaves out much): Categories, Topics, Sophistici Elenchi, Analytics, Metaphysics Δ, the physical works, the Ideals, and the rest of the Metaphysics.[5] Many modernistic scholars, yet, based simply on lack of evidence, are skeptical of such attempts to determine the chronological society of Aristotle's writings.[six]

Logical writings

- Organon (collected works on logic):

- (1a) Categories (or Categoriae)

- (16a) De Interpretatione (or On Interpretation)

- (24a) Prior Analytics (or Analytica Priora)

- (71a) Posterior Analytics (or Analytica Posteriora)

- (100b) Topics (or Topica)

- (164a) Sophistical Refutations (or De Sophisticis Elenchis)

Physical and scientific writings

- (184a) Physics (or Physica)

- (268a) On the Heavens (or De Caelo)

- (314a) On Generation and Corruption (or De Generatione et Corruptione)

- (338a) Meteorology (or Meteorologica)

- (391a) On the Universe (or De Mundo, or On the Creation)*

- (402a) On the Soul (or De Anima)

- (436a) Parva Naturalia (or Niggling Physical Treatises):

- Sense and Sensibilia (or De Sensu et Sensibilibus)

- On Memory (or De Memoria et Reminiscentia)

- On Sleep (or De Somno et Vigilia)

- On Dreams (or De Insomniis)

- On Divination in Sleep (or De Divinatione per Somnum)

- On Length and Shortness of Life (or De Longitudine et Brevitate Vitae)

- On Youth, Erstwhile Historic period, Life and Death, and Respiration (or De Juventute et Senectute, De Vita et Morte, De Respiratione)

- (481a) On Breath (or De Spiritu)*

- (486a) History of Animals (or Historia Animalium, or On the History of Animals, or Description of Animals)

- (639a) Parts of Animals (or De Partibus Animalium)

- (698a) Motion of Animals (or De Motu Animalium)

- (704a) Progression of Animals (or De Incessu Animalium)

- (715a) Generation of Animals (or De Generatione Animalium)

- (791a) On Colors (or De Coloribus)*

- (800a) On Things Heard (or De audibilibus)*

- (805a) Physiognomics (or Physiognomonica)*

- On Plants (or De Plantis)*

- (830a) On Marvellous Things Heard (or De mirabilibus auscultationibus)*

- (847a) Mechanics (or Mechanica or Mechanical Bug)*

- (859a) Issues (or Problemata)

- (968a) On Indivisible Lines (or De Lineis Insecabilibus)*

- (973a) The Situations and Names of Winds (or Ventorum Situs)*

- (974a) On Melissus, Xenophanes, and Gorgias (or MXG)* The section On Xenophanes starts at 977a13, the section On Gorgias starts at 979a11.

Metaphysical writings

- (980a) Metaphysics (or Metaphysica)

Ethical & Political writings

- (1094a) Nicomachean Ethics (or Ethica Nicomachea, or The Ethics)

- (1181a) Magna Moralia (or Dandy Ideals)*

- (1214a) Eudemian Ideals (or Ethica Eudemia)

- (1249a) On Virtues and Vices (or De Virtutibus et Vitiis Libellus, Libellus de virtutibus)*

- (1252a) Politics (or Politica)

- (1343a) Economics (or Oeconomica)

Aesthetic writings

- (1354a) Rhetoric (or Ars Rhetorica, or The Fine art of Rhetoric, or Treatise on Rhetoric)

- Rhetoric to Alexander (or Rhetorica advertizing Alexandrum)*

- (1447a) Poetics (or Ars Poetica)

Major current editions

- Princeton University Press: The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation (2 Volume Prepare; Bollingen Series, Vol. LXXI, No. 2), edited by Jonathan Barnes. ISBN 978-0691016511 (the almost complete contempo translation of Aristotle'south extant works, including a choice from the extant fragments)

- Oxford University Printing: Clarendon Aristotle Series.

- Harvard University Printing: Loeb Classical Library (hardbound; publishes in Greek, with English translations on facing pages)

- Oxford Classical Texts (hardbound; Greek only)

Notes

- ↑ W.T. Jones, The Classical Mind: A History of Western Philosophy (Harcourt Caryatid Jovanovich, 1980), 216.

- ↑ Marcus Tullius Cicero, Flumen orationis aureum fundens Aristoteles. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ↑ Will Durant, The Story of Philosophy (Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1926, ISBN 9780671739164), 92.

- ↑ Jonathan Barnes (ed.), The Complete Works of Aristotle (Princeton Academy Printing, 1984).

- ↑ W.D. Ross, Aristotle's Metaphysics (1953).

- ↑ Jonathan Barnes, "Life and Work," in The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle (1995) eighteen-22.

References

ISBN links back up NWE through referral fees

- Ackrill, J.L. Essays on Plato and Aristotle, Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0585128278.

- Adler, Mortimer J. Aristotle for Everybody. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1978. ISBN 0025031007.

- Bakalis Nikolaos. Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments. Trafford Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1412048435.

- Barnes J. The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle. Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0521411335.

- Bocheński, I.M. Ancient Formal Logic. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company, 1951.

- Bolotin, David. An Approach to Aristotle's Physics: With Particular Attending to the Role of His Way of Writing. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1998. ISBN 0585092052.

- Burnyeat, G.F., et al. Notes on Volume Zeta of Aristotle's Metaphysics. Oxford: Sub-faculty of Philosophy, 1979.

- Chappell, V. "Aristotle'south Conception of Matter," Periodical of Philosophy seventy (1973): 679-696.

- Code, Alan. "Potentiality in Aristotle's Science and Metaphysics," Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 76 (1995).

- Durant, Volition. The Story of Philosophy. Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1926. ISBN 978-0671739164.

- Frede, Michael. Essays in Ancient Philosophy. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. ISBN 0816612749.

- Gill, Mary Louise. Aristotle on Substance: The Paradox of Unity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0691073347.

- Guthrie, W.Thousand.C. A History of Greek Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0521387606.

- Halper, Edward C. One and Many in Aristotle's Metaphysics. Parmenides Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-1930972216.

- Irwin, Terence. Aristotle's First Principles. New York, NY: Oxford Academy Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0198242901.

- Jones, W.T. A History of Western Philosophy: The Classical Mind. Wadsworth Publishing, 1969. ISBN 978-0155383128.

- Jori, Alberto. Aristotle. Milano: Bruno Mondadori Editore, 2003. ISBN 8842497371.

- Knight, Kelvin. Aristotelian Philosophy: Ethics and Politics from Aristotle to MacIntyre. Polity Press, 2007. ISBN 0745619762.

- Lewis, Frank A. Substance and Predication in Aristotle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0521391598.

- Lloyd, G.E.R. Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968. ISBN 0521094569.

- Lord, Carnes. Introduction to The Politics, by Aristotle. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1984.

- Loux, Michael J. Primary Ousia: An Essay on Aristotle'south Metaphysics Ζ and Η. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Academy Printing, 1991. ISBN 0801425980.

- Owen, G.E.L. "The Platonism of Aristotle," Proceedings of the British University l (1965): 125-150. Reprinted in J. Barnes, Yard. Schofield, and R.R.Chiliad. Sorabji (eds.), Articles on Aristotle, Vol 1. Scientific discipline. London: Duckworth (1975). 14-34

- Pangle, Lorraine Smith. Aristotle and the Philosophy of Friendship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing, 2003. ISBN 0521817455.

- Reeve, C.D.C. Substantial Knowledge: Aristotle's Metaphysics. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 2000. ISBN 0872205150.

- Rose, Lynn E. Aristotle'southward Syllogistic. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, 1968.

- Ross, Sir David. Aristotle, 6th edition. London: Routledge, 1995. ISBN 9780415120685.

- Ross, W.D. Aristotle'southward Metaphysicss. Stilwell, KS: Digireads, 2006. ISBN 978-1420927498.

- Scaltsas, T. Substances and Universals in Aristotle's Metaphysics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Academy Printing, 1994. ISBN 0801430038.

- Strauss, Leo. "On Aristotle'southward Politics," in The City and Man. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Printing, 1978. ISBN 978-0226777016.

- Taylor, Henry Osborn. "Chapter three: Aristotle's Biology," Greek Biology and Medicine - 1922. Ithica, NY: Cornell University Library, 2009. ISBN 978-1112301230.

- Veatch, Henry B. Aristotle: A Contemporary Appreciation. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1974. ISBN 0253308909.

- Woods, K.J. Universals and Particular Forms in Aristotle's Metaphysics. Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy supplement, 1991.

Note: This article incorporates material from Aristotle on PlanetMath, which is licensed under Creative Commons CC-past-sa 3.0.

External links

All links retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Works by Aristotle. Project Gutenberg.

- References for Aristotle.

- Works past Aristotle at Perseus Projection.

- Some of Aristotle's works: Analytica Priora & Posteriora, Poetics (All in Greek).

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy articles on Aristotle's works:

- "Biology"

- "Causality"

- "Ethics"

- "Logic"

- "Mathematics"

- "Metaphysics"

- "Natural Philosophy"

- "Political Theory"

- "Psychology"

- "Rhetoric"

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "Aristotle"

- Aristotle—Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Aristotle at the Free Library.

- Large drove of Aristotle'southward texts, presented folio past folio.

Full general philosophy sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Cyberspace Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

| Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| Topics | Category listings | Eastern philosophy · Western philosophy | History of philosophy(ancient • medieval • modern • contemporary) |

| Lists | Basic topics · Topic list · Philosophers · Philosophies · Glossary · Movements · More lists |

| Branches | Aesthetics · Ethics · Epistemology · Logic · Metaphysics · Political philosophy |

| Philosophy of | Education · Economics · Geography · Data · History · Human nature · Language · Constabulary · Literature · Mathematics · Listen · Philosophy · Physics · Psychology · Religion · Scientific discipline · Social scientific discipline · Technology · Travel ·War |

| Schools | Actual Idealism · Analytic philosophy · Aristotelianism · Continental Philosophy · Critical theory · Deconstructionism · Deontology · Dialectical materialism · Dualism · Empiricism · Epicureanism · Existentialism · Hegelianism · Hermeneutics · Humanism · Idealism · Kantianism · Logical Positivism · Marxism · Materialism · Monism · Neoplatonism · New Philosophers · Nihilism · Ordinary Linguistic communication · Phenomenology · Platonism · Positivism · Postmodernism · Poststructuralism · Pragmatism · Presocratic · Rationalism · Realism · Relativism · Scholasticism · Skepticism · Stoicism · Structuralism · Utilitarianism · Virtue Ideals |

| Topics about Ancient Greece | |

|---|---|

| Places | Aegean Ocean • Hellespont • Macedon • Sparta • Athens • Corinth • Thebes • Thermopylae • Antioch • Alexandria • Pergamon • Miletus • Delphi • Olympia • Troy |

| Life | Agronomics • Fine art • Cuisine • Economy • Law • Medicine • Paideia • Pederasty • Pottery • Prostitution • Slavery • Applied science • Olympic Games |

| Philosophers | Pythagoras • Heraclitus • Parmenides • Protagoras • Empedocles • Democritus • Socrates • Plato • Aristotle • Zeno • Epicurus |

| Authors | Homer • Hesiod • Pindar • Sappho • Aeschylus • Sophocles • Euripides • Aristophanes • Menander • Herodotus • Thucydides • Xenophon • Plutarch • Lucian • Polybius • Aesop |

| Buildings | Parthenon • Temple of Artemis • Acropolis • Aboriginal Agora • Arch of Hadrian • Temple of Zeus at Olympia • Colossus of Rhodes • Temple of Hephaestus • Samothrace temple complex |

| Chronology | Aegean civilisation • Minoan Culture • Mycenaean civilization • Greek dark ages • Classical Greece • Hellenistic Greece • Roman Greece |

| People of Note | Alexander The Great • Lycurgus • Pericles • Alcibiades • Demosthenes • Themistocles |

| Art and Sculpture | Kouroi • Korai • Kritios Boy • Doryphoros • Statue of Zeus • Discobolos • Aphrodite of Knidos • Laocoön • Phidias • Euphronios • Polykleitos • Myron |

| Logic | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main articles | Reason · History of logic · Philosophical logic ·Philosophy of logic · Mathematical logic · Metalogic · Logic in information science | ||||||||||||||

| Key concepts and logics |

| ||||||||||||||

| Controversies | Paraconsistent logic · Dialetheism · Intuitionistic logic · Paradoxes · Antinomies · Is logic empirical? | ||||||||||||||

| Key figures | Aristotle · Boole · Cantor · Carnap · Church · Frege · Gentzen · Gödel · Hilbert · Kripke · Peano · Peirce · Putnam · Quine · Russell · Skolem · Tarski · Turing · Whitehead | ||||||||||||||

| Lists | Topics(basic • mathematical logic • bones discrete mathematics • ready theory) · Logicians · Rules of inference · Paradoxes · Fallacies · Logic symbols | ||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia commodity in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Artistic Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that tin can reference both the New Earth Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click hither for a list of adequate citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is attainable to researchers here:

- Aristotle history

The history of this article since information technology was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Aristotle"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to utilise of private images which are separately licensed.

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Aristotle

0 Response to "Aristotle Argue Both Science and Art Can Express Universal Truths"

Post a Comment